Oh, come on. Did anyone seriously think that I would not buy and review this book immediately, as soon as it came out, with great fanfare and excitement? It’s the latest Dear Canada installment!

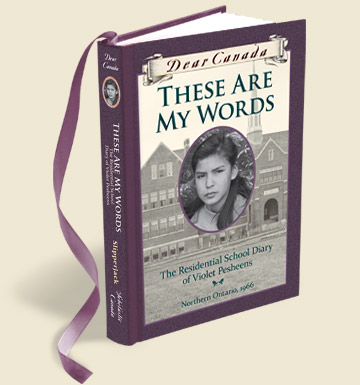

These Are My Words: The Residential School Diary of Violet Pesheens, Northern Ontario, 1966, Ruby Slipperjack, 2016.

Ruby Slipperjack, the author, is a survivor of a residential school herself, and this book is based loosely on her experiences of growing up in a remote area and going to a city school beginning in Grade Five. When I heard DC was putting out a book about residential schools, I was super excited, but I also thought they would be setting it on the prairies between, oh, the 1880s and 1930s or so, which I think is what people tend to associate with the “classic” residential schools experience. But, rightly, Scholastic Canada probably figured they had a bunch of books set during that time period, and they were due for one set in a more recent period and they could focus on the residential school experience in the “modern” era, which is a lot less popular. Although it has been gaining some media exposure with the movement towards reconciliation, I think it forms much less of the popular conception.

I’m not going to do a full recap of this book, because it’s so new and I don’t want to spoil it, but it was shockingly, astoundingly hard to read in places, and amazingly different in tone from any other book in any other Dear America/Dear Canada/Royal Diaries/I Am Canada/My Name Is America/etc. series that I’ve ever read. I think the only one that it even comes close to in tone is Where Have All The Flowers Gone?, the Vietnam War era DA novel, and that’s only because it deals with some slightly mature themes in roughly the same time frame. But this book is so much more intense than that. Not in the sense that it has an extraordinarily heavy plot—in fact, it’s fairly light on the plot—but the subject matter is hardcore.

It really doesn’t pull any punches, either. The very first line in this book is “They took everything away when I arrived here.” Just in case you thought this would be a cheery book. I’ve felt for a long time that Dear Canada is a higher caliber series than Dear America, because I do feel that the books are more well-written and deal with heavier subject matter. The DA books are good, don’t get me wrong, but the DC books have orphans, people dying left right and centre (and main characters, too!), protagonists being imprisoned, all kinds of stuff. I haven’t been a huge fan of their most recent offerings, which is why I haven’t gotten around to reviewing yet, but there is an absolutely gut-wrenching novel, Pieces of the Past, which is about a Holocaust survivor who’s been sent to Winnipeg after losing her entire family in the camps. That, and this book, are why I think that Dear Canada is more intense overall. Those are some hard-core fucking books.

Anyway, Violet is sent from her home to a residential school where the Indian students will live while attending a white school in the city. (It’s actually not mentioned explicitly where the school is, but Violet grows up in Flint Lake.) They’re not to speak in anything other than English ever, and they have all their clothes taken and their hair cut and they live in dorms, all together, but are forbidden to basically have any fun. There’s a lot of suppressed strain in this book—we learn that Violet lives with her grandmother rather than her mother, stepfather, and two half-siblings, but we never learn exactly why that’s so, and it’s just implied that there’s some family strife. Violet’s father is never in the picture, ever. But again, this is all mostly subtextual, which is really well done but pretty intense for a kids’ book. I mean, here is a quote. “Just because my mother married him doesn’t mean she pushed me aside…Yeah, I think it was me that made the home at the Reserve not always happy. I just never fit in…” at home. I’m dying.

One of the funny things about this book is that it’s the most modern of the Dear Canada books, so it has all these amusing asides—Violet’s been on airplanes, she watches Ed Sullivan on the television, she listens to the Beatles and the Monkees, they eat peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches and candy bars, all that kind of thing. Which is a nice and uplifting touch in a super depressing book.

Anyway, basically Violet is super depressed because she doesn’t know anyone there, and also it’s a horrible place. The only OK thing about it is the food, and Violet points out that a lot of the girls there gain weight all year and then lose it in the summer because at home there isn’t always enough food to go around, and the food that’s there isn’t as calorically dense as what they’re given at the school. And basically everything is horrible—a white man in a car pulls up besides Violet and offers to take her for a ride. “I had no idea danger came from people in cars. I knew that a car will kill you if it hits you, but I did not know a driver was dangerous too!”

And another thing that I think is really well handled is that Violet is an angry, mean protagonist. “I get very angry sometimes and I don’t know why. It’s like a burning pain across my chest. I never used to get angry…now I’m angry all the time.” I am not emotionally equipped for this now and I’m twenty-eight! You know, I think this is one of those DC/DA books that definitely skews for an older audience. Although Violet is just twelve during this book, but it’s just…intense. I know I keep using that word over and over again, but good God, Ruby Slipperjack packs an awful lot of emotion and feeling into 161 pages. Violet beats up an older girl and pushes her to the ground and holds a BROOM against her THROAT. This is some heavy fucking stuff for a book series targeted at 9-12-year-olds!

One of the other things in this book is that Violet talks, explicitly, about her changing body. This may be the only one where a protagonist openly gets her period (and hates it, obviously—“I was very dismayed that this would happen every month for one whole week!”—get in line, sweetheart, we were all dismayed to learn that) and needs a bra. It has the word “tits!” ! ! ! I’ll freely admit I haven’t read all the My Name Is America/I Am Canada books, although I will eventually, but I don’t know if “tits” appears in any of those books, either. Anyway, it’s really well handled—it’s important enough that Violet writes it down but it’s not something that really, really impacts her life—which is I think pretty true to life for most girls.

Like I mentioned, there isn’t a whole lot of plot-plot here–it’s basically just one school year for Violet, and how she’s lonely and confused a lot and how the tiny little bits of comfort (dinner, a letter from home, watching television) don’t add up to enough to make anyone happy. It’s like that in the whole school there’s maybe a whole person’s worth of happiness, but it’s being split across a hundred kids and they’re all just grabbing at scraps. “I am feeling like I am stuck on a very long mourning period where you cannot start crying for a person who died and you have to wait for the right time. My heart and soul is starting to hurt. I can’t get rid of that feeling. I just want to start crying and get out of here and go home!!!”

She makes friends with a couple of other girls, she goes to help another girl babysit in a white family’s home, some other girls steal her letters from home—that kind of thing. It is explained that part of the reason that Violet’s family is splintered is because when her mother was five, the “Government” took her to a residential school by threatening her parents with prison—and then when she came home, “I came along.” Which is a nice, if subtle way, of showing how residential schools managed to fuck up family lines across generations.

The kids are not allowed to go home for Christmas, because one girl comes down with German measles. Every student is miserable and crying, except for one girl who’s super psyched not to go home, and says “I get to avoid Christmas at home this year. People kill each other at Christmas where I come from. We are always so scared. I had to hide under the bed with my tow little sisters for almost a whole day last year. It’s just so…” Alcoholism is a hell of a thing around the holidays. I’m not sure if there’s another DA/DC book that addresses alcoholism even tangentially like this one.

“I keep getting very frustrated, then I get angry. I can’t take much more of this. I want to go home! I had another crying fit last night. I woke up from a nightmare…I had a hard time going back to sleep.” Violet worries that she’s forgetting all of the Anishnabe she knows because she’s not allowed to speak it to anyone there, which terrifies her.

They’re all allowed to go home for Easter since they missed their Christmas, but aren’t allowed to take anything with them. Violet smuggles her diary home under her clothes, but she doesn’t care about anything else since she gets to see her grandmother again. She figures out that she hasn’t been receiving the letters or money her grandma sent more than once—someone was opening the letters along the way and taking them—but most importantly, when it comes time to head back, Violet says she doesn’t want to go back. They figure out that Violet can’t stay with her grandmother, because the Indian Affairs people know where she lives, but if she goes to stay with her mother on the reserve, she can go to the school there and finish Grade Five over again rather than go back to the residential school.

Living on the reserve is a big change for Violet—she’s still not too crazy about staying there, but she starts learning to cook with cookbooks. Once she finishes Grade Five, though, she’ll be sent to the city again but instead she’ll live in white people’s homes, rather than in the school. “I really have no choice and no say as to where I am being sent or where I will stay. They will just get us on a plane, then onto a train and then into a city to be dropped off at white people’s homes….I’m really not happy about this, but I notice the other kids are all excited about going into the city! Idiots!!!” She’s twelve. Can you imagine being twelve or thirteen years old and being sent from the place you’ve lived your whole life to live with total strangers while you go to school? Everything about this is horrible.

In the epilogue, Violet goes to high school and her grandmother dies when she’s in her final year, which is a horrible blow. She returns to the reserve after she graduates and gets married to a teacher, and they have four children.

Rating: A. This is such a hard, hard book to read. It’s good, and it’s important, and I love how it handles some really difficult topics with grace, but wow. It’s hard to plow through 161 pages of really depressing book. And it doesn’t even have an uplifting ending! (This is not a complaint, by the way.) The ending is worse, if that’s possible! Just…I’d recommend this book for older readers, but I really don’t know if I’d be happy to have kids under eleven or twelve reading it. And even then I wouldn’t be surprised if some kids of that age had a hard time handling it. On the other hand, while I’m spitballing, it might be easier for kids—maybe it’s just so hard for me to read it as an adult, looking back, with the whole context of the residential schools and splintered family dynamics to understand? Who knows. Read this book. I’ll lend you my copy.

Wow, that sounds like quite a book!

LikeLike

It REALLY is! So worth the read!

LikeLike

I think these heavy issues are actually somewhat easier for kids to deal with than for us – sometimes I think back on books I read in elementary school and am amazed at how dark they are. (Nearly all of Diana Wynne Jones’s books are like this.)

LikeLike

That’s true, and I would have been incredibly interested to see what my own reaction to this book would have been as a kid. I think I probably wouldn’t have been nearly as horrified as I was! But as an adult with the full weight of historical impact behind it, it’s AWFUL.

LikeLike

One of my daughters loves Dear Canada – she’s 12 – I will get her this book and report her reactions. Great review. I wonder if you might review some of the Deborah Ellis books – I realize the Breadwinner series is kinda recent time-wise, but it’s so good! Also her Company of Fools is a favorite.

LikeLike

A field report! I love it!

I actually have not read any of her books but I have heard great things about them! I’ll put them on the list and hopefully my library will have a good supply!

LikeLike

So…an update! We managed to snag the book at our local Scholastic fair, and after reading the book in a solid stretch one day off from school, my twelve year old says:

“I loved it! For a younger kid, it would be tough, but for a mature reader, no. It shows loss – which some kids aren’t able to handle, and it shows how much the schools changed the kids – like oh my goodness! Some parts made me laugh – the sorta deadpan stuff (and here she looked up a part from p. 150) – where Violet’s grandma asks if she wants to go back to residential school, and Violet says no – and just leaves the rest of everything unsaid. She just sounds like me – like what can you say?”

She then went on to talk about other parts of the book that provoked her reactions – the cookbook, the boys chasing Violet, David pushing his dust over into her area she was supposed to clean, etc.. Mom’s prompts and clarifying questions excluded from the above!

I think what I like about my daughters’ reaction (besides the fact that she calls herself a mature reader) is that she clearly found Violet relatable and interesting. She saw her as a complex girl like any other girl, who had to cope with horrendous circumstances. So although we as a family learn a lot about history, I’m glad the person stood out here – that history and in particular the history of First Nations is not about pawns on a chess board but real people – a testament to Ruby Slipperjack’s writing. (Now I will go and look up her other books!)

LikeLike

This is amazing. Thank you so very much–I love this and I’m so happy both of you found it worthwhile and moving! Thank you!

LikeLike

You … may be interested to know that, as a direct result of your post, this book is going on at least one Top-25 research university’s Children’s Lit syllabi starting next year.

LikeLike

OH MY GOD THIS IS THE BEST NEWS EVER EVER EVER EVER

THANK YOU, YOU’VE MADE MY WEEK!!!!

LikeLike

Pingback: 2016 In Review | Young Adult Historical Vault

Pingback: My Heart Is On The Ground | Young Adult Historical Vault

Pingback: A Time for Giving | Young Adult Historical Vault

I read it. IT’S SO SAAAAAAAAAD

LikeLike