I should just rename this blog “Watch Me Torture Myself With Terrible Books.”

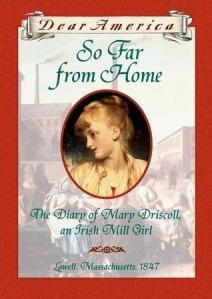

So Far From Home: The Diary of Mary Driscoll, an Irish Mill Girl, Lowell, Massachusetts, 1847, Barry Denenberg, 1997.

If you see that name in the title you can probably figure out what my verdict is going to be, but let’s do this anyway. My main problem with this book is that Denenberg has created a terribly stereotypical character who even writes using a vague dialect. It’s all very strange and dreamy and kind of terrible all at the same time.

Mary is a fourteen-year-old girl from Skibbereen, in the extreme south of Ireland, where she lives with her parents. They are very slowly starving to death on account of the potato famine, but Mary’s older sister Kate has gone to America two years beforehand to live with their aunt Nora near Boston. There’s a very brief bit on the first page about how Nora taught Mary English, but this is never spoken of ever again, and while I don’t know how many people in Cork were speaking Gaelic as a first and only language in 1847, Mary’s theoretical English-as-a-second-language never comes up ever again. So.

Anyway, Nora spends all her time telling Mary stories about mermaids and stuff, and then smash cut to the present where Nora has sent a ticket for Mary to come and join her and Kate. Mary’s father is pretty bitter about this (as he would be, having lost everything including now both his daughters), but she vows to make enough money to bring her parents over too. Kate has sent them nothing, which seems awfully cold, since she works as a maid to a mill owner. At the end of April, Mary says goodbye to her parents and sets off for the port at Cork.

When she gets on board the ship, she befriends a couple from Killarney, the O’Donnells, who are going to meet their daughter in America. They befriend another family, the Corcorans, with twin daughters and a son, and all of them share their food and spend their time together. Mary looks after the children, since Brendan is homesick and miserable, and then Mr. O’Donnell comes down with ship fever (i.e., typhus). Mary meets a young man, Sean Riordan, who tells her about his uncle in Boston and a bit about the mills.

There’s a very weird segment where in the entry dated May 20th, Mary notes that Mr. O’Donnell I worse and worse, and then on the 26th she writes “I fear I have gotten the ship fever. First Mr. O’Donnell, and now will it take me, too? ‘Twas nothing anyone could do for him…” and then they put him out to sea. It’s very strangely-written and not very clear! But Mary survives the fever (obviously) and then two days later Mrs. O’Donnell dies of the ship fever, too. So Mary tells Sean that when they get to Boston, they have to find their daughter and make sure she’s looked after properly.

Near the end of June they see land and make harbour in Boston, at last. The immigration officers inspect everyone on the ship, and Mary winds up on the pier feeling terribly lonely. Her aunt doesn’t come to pick her up, so Sean’s uncle insists she accompany them both home. They find that Alice O’Donnell has been living not too far away, in the cellar of a family and doing their wash for her living. But Alice is blind and has clearly been treated horribly, so Sean’s uncle takes her home until they can find an actual decent place for her to live. This is a very nice little story but I have no idea what it has to do with the rest of the plot, other than to illustrate that Irish girls had a very hard time? But why did the O’Donnells send their daughter to America alone? Was she blind the whole time, or did she go blind? What? Nothing about this makes sense.

Anyway, Kate comes to fetch Mary eventually and takes her back to Lowell, and natters on about her amazing job as a maid to Mrs. Abbott. Mary is hired on in the mills to start in the spinning room, and she’s very pleased to see that her aunt Nora has changed very little. Nora’s boarders, Mrs. Delaney and her son John who is a bit addled in the head, don’t contribute enough to make ends meet, so Nora is pleased to have Mary there for more reason than one.

Also, we learn that Aunt Nora speculates that Alice O’Donnell’s parents must have thought she would be better off in America, and probably sent her with someone who didn’t survive the voyage. But still. Why is this included? The story of Mary is depressing enough, I swear.

In the mills, Mary is horrified by the endless noise and hundreds of machines in the mills, but she is supposed to be a “bobbin girl,” to change bobbins on the spinning frames, which is a fairly simple job. One of the other girls, Annie, shows her the ropes.

And then Mary just flat-out stops writing about the mills. For two weeks she says nothing other than the noise is terrible and makes her head ache, and that she would like to be promoted to a spinner, for more money. In August she gets promoted. Seriously. There is nothing but big blank spaces where she’s not talking about the mills, or much of anything else other than how her aunt is feeling better. She meets up with Annie going for a walk and befriends her, and when she visits Annie at her boarding house, she meets up with several of the other girls who live there and work in the mills.

There’s a few bits here and there about how the Irish are persecuted—a little girl has rocks thrown at her, Sean has trouble finding work, etc., but it’s so minor that it’s hard to tell if they’re really going for a “experience of Irish persecution” thing or just “here are some interesting notes and details.” The mills are a terrible place, where it’s hot and miserable and girls get hurt, but there’s no depth to any of this! There’s no feeling behind it. It’s a blank, empty retelling of details about working in the mills, with an overlay of “’Tis” and “Twas” and it’s just devoid of any actual feeling.

Clarissa, one of Annie’s boardinghouse-mates, dislikes Mary and the Irish in general. Mary catches Clarissa imitating her and mocking her and the “shanty Irish,” and asks her if she would stay in a place where everyone was starving to death. Apparently, Clarissa and the other American girls hate the Irish for flooding the market with labour and forcing the wages down, but Mary points out that they would like a shorter day and more pay and all that stuff, too.

Anyway, Annie comes over to visit Mary’s house for her birthday, and Annie and Nora hit it off. Clarissa is caught sneaking around to see a boy. Mary gets a letter from Sean saying how difficult his work is and how much the bosses and locals hate the Irish. Clarissa gets scalped by one of the machines after refusing to tie up her hair—and then, as with everything else in this book, we never actually learn if she lives or dies! They carry her out of the mill, and we never hear anything about her again—is she dead? What?

Mary receives word that her parents have died, but she can’t do anything besides continue going to work and being depressed. She gets a letter from Sean’s uncle saying that Sean was involved in mob violence and was taken to jail, and he himself took Alice in to be sure she would be safe. Mary decides to go to Boston and take the money she’s been saving to bail out Sean, and one of Annie’s friends goes with her.

That’s the end. Seriously. In the epilogue we learn that Mary died in a cholera epidemic two years later at seventeen.

Rating: C-. I would have given this a flat D except for nostalgia. I don’t remember why I enjoyed it so much, though. It’s very flat, there’s no emotional depth to any of it, and the overlay of “Irish”-ness and weird aspects of the story that are picked up and dropped to eventually go nowhere—it all adds up to a pretty pitiful book.

I remember being really bothered by the fact that Clarissa’s FREAKING HORRIBLE injury was set up as Now This Is The Consequence of Vanity, Girls. Is that really a thing? Or did I just insert those overtones because I was in elementary school and accustomed to reading morals into things? In retrospect, it feels like the mill details were only there to set up the disturbing injury — “Oh, I need her in the spinning room so I can have a Vain Girl Gets Scalped scene, but she has to enter as a bobbin girl, so let’s shoehorn in a promotion here.”

Years and years after I read this book, my grandmother told me a story about the same thing happening to a girl she worked with in the late 1950s/early 60s, using a spinning tool that took runs out of panty hose. (I was briefly distracted by the fact that taking runs out of panty hose instead of just throwing them away had been a multiple-people-employing business.) Given that the girl that happened to survived — and for that matter, my wife just lost some hair to a power drill and was scared/very slightly embaldened but okay — the level of power that must have gone into those spinning machines is absolutely terrifying.

Your posts are such fun, even with the bad + kinda scary books!

LikeLike

You’re pretty correct. It’s very Clarissa Is A Bad Girl, who sneaks out to see boys, and makes fun of Irish girls: let’s punish her by RIPPING HER SCALP OFF.

Anyway, when I get around to it, there’s a Dear Canada book on child labour in spinning mills, where another character is brutally injured by a machine and it’s treated about 50 times more realistically, including PTSD, depression, and so on. This book is just WEAK.

LikeLike

Looking back, Mary’s reaction to Clarissa’s death was strangely cold. But at the time, I didn’t see the death itself as anything other than an illustration of the horrific dangers the girls were exposed to (and only a moral message in regards to the boss’s cold-blooded reaction). The TV episode based on this book handled it better, depicting Clarissa exactly as described but letting her survive after briefly getting her hair caught.

LikeLike